Parenting during a pandemic and remembering when I was a kid, when Mount St. Helens erupted

“Let’s get ice cream at King’s,” I suggested as Walter bounded down the school stairs, backpack in one hand, loose papers and his trumpet case in the other.

The week had left us both frazzled. A soft-serve swirl cone would fix everything, at least for a moment.

Sitting on our porch a few minutes later, cones in hand and trying to ignore the cold, I asked what he’s hearing about coronavirus at school.

He avoided my question, so I asked again.

“OMG it’s coming,” he answered, as if in air quotes, mimicking some pre-teen lilt he’s likely picked up from garbage TV shows, like Total Drama Island.

“Really,” I asked, nonchalant. “That’s what kids are saying?”

Sponsored

He’s 9-years-old, in fourth grade at a public school where he gets a healthy dose of current events, both in the classroom and on the playground.

“No, not really,” he said, halting, looking out across the street. “Yeah, they did,” he confessed a moment later. “Is it?”

The next day, the Seattle school district announced classes were cancelled for at least two weeks, in an effort to contain the outbreak. That closure would soon extend to six weeks, across the entire state. From there, the wave of closures and public health mandates would spread quickly across the country.

In the days and weeks leading up to this, Walter watched as both of his parents worked long hours, paced the room on late phone calls, and sat at their computers through the weekends. I’m an editor at KUOW, and our workplace went almost entirely remote the first week of March.

My husband has worked at The Stranger, Seattle’s alternative news weekly, for nearly 16 years, where many coworkers have become like a family to us. My work was ramping up to 24/7; his was watching its revenue evaporate overnight and making the heartbreaking ramp down to (hopefully temporary) layoffs.

Sponsored

I’ve been acutely aware of Walter witnessing our emotions, our abnormal schedules, our stress, our tense conversations, the news on the car radio. He appeared to take much of it in stride — the all-you-can-eat buffet of TV helped — but it clearly sunk in.

In the first few days I worked from home, he’d drop by my desk every couple hours to surprise me with a hug. One morning as I hunched over my laptop at the coffee table, he walked in with a plush blanket and pulled it over my legs.

“That always makes me feel better,” he said. I pulled him in for a big snuggle.

He often has trouble falling asleep and doesn’t like being alone at night, so it’s no surprise that bedtimes got a bit tougher.

He wants to sleep in our bed. He wants to make sure one of us stays awake until he’s asleep. He wants to have his favorite stuffed animal with him more often — a worn out giraffe named Pato. (Pato means duck in Spanish. Again, it’s a giraffe.)

Sponsored

A couple of nights ago, as I told him goodnight, he asked what seven items I’d take from our house if there were a fire. His first four items: Pato, the iPad (sigh), his wallet and his books.

He’s an easy-going kid; confident, social and a good travel buddy. But this past week, the younger child in him peeked through again. He cajoled us to stay up later and later one night to watch videos from his toddler days. He crawled in bed with me one weekend — shoving my laptop aside — and asked to play an imagination game we hadn’t played since preschool: Squirrel Coffee Shop, where we pretend to be squirrels who run a coffee shop.

Saturday morning, I suggested we put on some music as we made pancakes. He’d typically pick a pop song you might hear on Disney Radio, or something from his latest obsession, a musician known as TheFatRat. But instead, he asked Alexa to play the theme song from Caillou, a Canadian show aimed at the pre-school set.

“I'm just a kid who's four,

Each day I grow some more,

Sponsored

I like exploring,

I'm Caillou.”

Clearly, this anxious season is taking a toll. If he’s looking for comfort and security, I want to help him find that in any way possible.

We’ve listened to some really helpful kid-targeted podcasts and news together, which helped break down some questions about coronavirus. We talk about washing hands, covering our coughs, why school is out and why we’re not visiting grandparents. One of his close friends has been battling leukemia for the last few years, so we know well that although most kids don’t get sick, some are more vulnerable.

And I’m thinking intensely about the ways this childhood experience could stay with him, and the way a crisis in my early childhood stayed with me: the eruption of Mt. St. Helens on May 18, 1980.

Sponsored

Once I became a parent, I thought back a lot to that experience and felt a hole in my memory for how we navigated it as a family. I mostly remember my fear and the adults buzzing around me and feeling like nobody ever told us kids what was going on. I want Walter’s experience to be different. And maybe my experience was different at the time but my memory tells another story.

It was a Sunday, after church, I was seven years old. We lived in a town I’d describe for the rest of my life as “a tiny truck stop town about an hour west of Spokane, full of churches, wheat farms and not much else.” Here’s how HistoryLink.org describes it, in the aftermath of the eruption:

Ritzville was directly in the path of the ash cloud on May 18, 1980, and was hit harder than nearly any other spot in Eastern Washington. Four to six inches of ash covered every surface, with drifts as high as two feet. When the mountain blew, thousands of motorists traveling cross-state on weekend excursions...were forced to pull into Ritzville when visibility was reduced to nothing.

Ritzville's motels were quickly overmatched. Hundreds of people were herded into the school gymnasium, which quickly filled. By the end of the day, crowds were gathered in every restaurant and church. Residents opened up their homes. Ritzville's 20-bed hospital was crowded with people suffering from respiratory problems -- and the hallways were jammed with those who had nowhere else to go.

The hospital's director of nursing said she was "seeing quite a bit of mass panic because you can't move." She said the "wind is blowing so hard that it burns your throat and eyes" whenever you take a step outside.

My mom was a nurse at that hospital. Maybe that’s why I can’t really picture her with us much in those hours.

Walking home from church that day, I remember seeing our neighbor perched on the sidewalk, his telescope on a tripod pointed toward the descending gray sky. He invited my dad to take a look. I stayed at his side, silent and ignored. This view was clearly only for grown-ups.

My family of six had walked the two blocks from church in our usual scatter, and when we arrived home, after the adults-only telescope detour, we realized we were missing my little brother Gabe, age 5.

We quickly searched our compact home. No sign of Gabe in the bedrooms, in the bathroom, in the creepy side attic or cement basement where mom put up her canned fruits and vegetables and dad hung his boxing bags. No Gabe.

My parents called out, over and over, and somehow it was all our fault. All of us kids, I mean. We didn’t look after him. What were we thinking?

But how could we look after him on this Sunday when the noon sky had turned to blackness. When the rapture and end times were clearly upon us, and nobody was telling us anything?

Gabe was later found hiding in a neighbor’s garage; he had become disoriented when the ash cloud turned the day to night and took cover in the first place he could find.

In the coming days, we stayed indoors and watched the National Guard pour into town and sweep the ash off of our sagging garage roof. I remember a lot of people in cheap face masks. At some point we were able to leave town to go stay with my aunt Patsy in Fort Lewis, on the other side of the state. I remember we got to go to Wild Waves waterpark on that trip. Amazingly, we forgot to get Gabe into the car as we headed out that day and had to turn off the highway to go retrieve him. Poor Gabe.

The fear of that day stayed with me. The silence of that time, even more. Why didn’t my parents talk more with us kids about the eruption? What could they have done or said to reassure me, to connect with me, to hear me? If they did -- and they must have, we were a close and loving family -- why do I not remember?

So for you, Walter, in this time when we are again seeking cover and wearing masks, I want your memories to come out differently. We’re all still figuring this out, but here’s where I will start:

We will talk. I will make space for your questions as things come up. I will listen.

We will write or record something together, so when you look back on this later you’ll remember how we navigated as a family. You’ll have a voice in your own memories.

We’ll have fun. We’ll relax the rules. You can stay up late or eat cereal for dinner sometimes. It will be an adventure with many light moments and playfulness.

We will keep things normal, kind of, when we can. You’ll practice piano, play with friends (online for now), do some homework.

We’ll find new ways to handle this distance with the people we love. We’ll do video calls and send letters and maybe you’ll finally get that YouTube channel you keep begging for.

We’ll be straight with you when you want answers. We will tell you the truth.

We will embrace the weirdness of this time and ask how we can help. We’ll reach out to our neighbors and show kindness whenever possible, especially to each other.

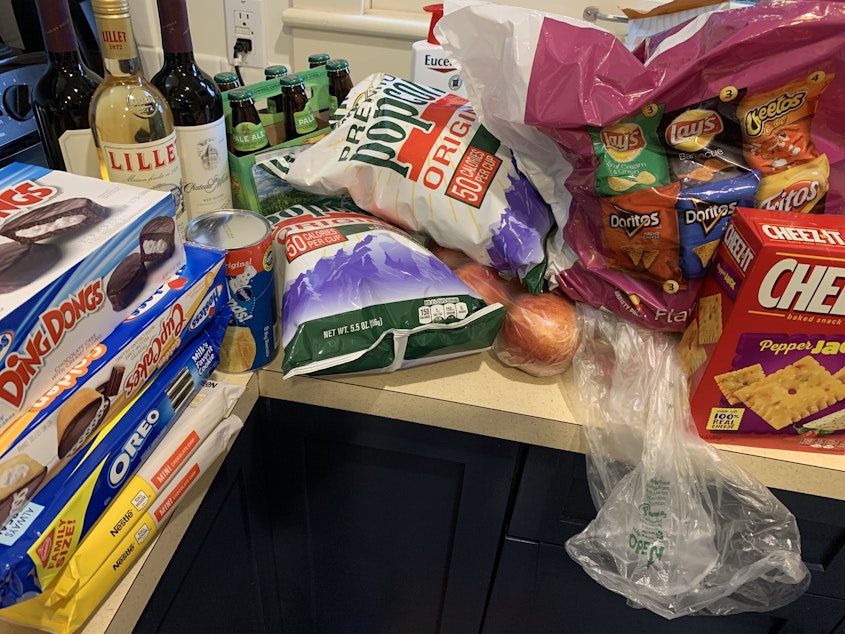

And we’ll probably get tummy aches from all the cupcakes and Ding Dongs I stockpiled in the pantry this weekend; some childhood comforts never get old.