White kids usually get the most recess in Seattle. Black kids, the least

A KUOW investigation shows that in Seattle Public Schools, poor kids and children of color tend to get much less recess than kids at mostly white, well-off schools.

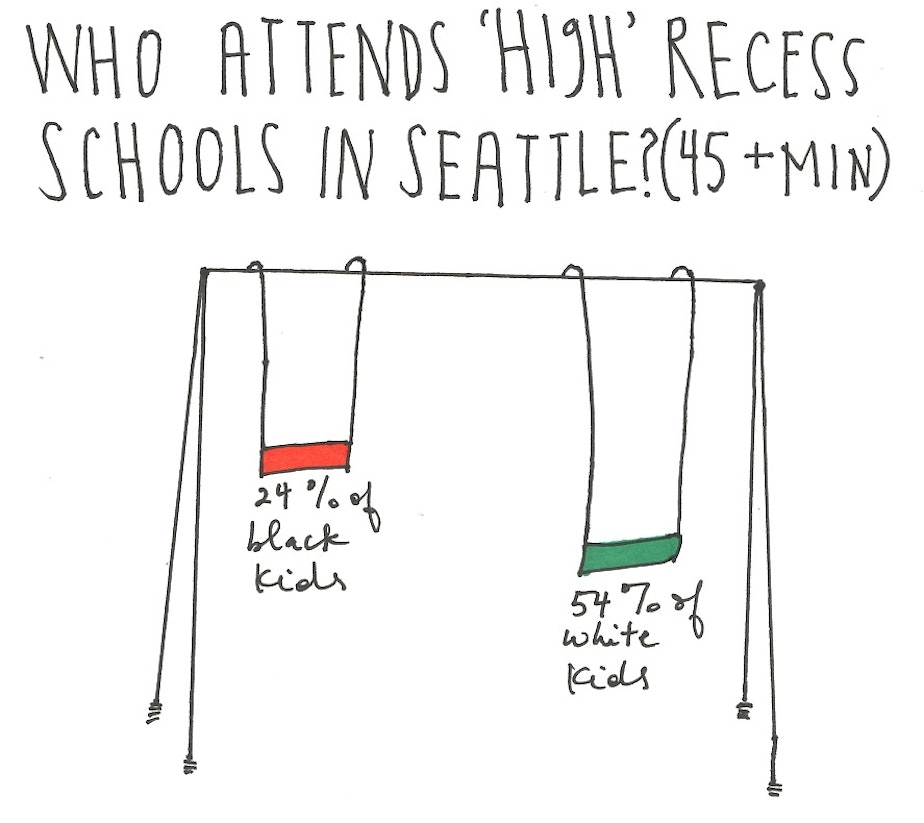

In Seattle, white kids typically get more recess. Black kids get less.

A KUOW investigation found that kids at schools that schedule 30 minutes of recess for everyone – the minimum allowed – are more likely to be poor, children of color, and learning English. Schools that average 45 minutes of recess or more have whiter, wealthier student populations.

That gap is troubling to those who research the value of recess for physical and emotional health – and what recess does for kids back in the classroom.

"Physical activity has been shown to improve academic performance,” said Dori Rosenberg, a researcher at the Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute. “It improves attention and concentration.”

The World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and American Academy of Pediatrics all say that one hour is the minimum amount of moderate-to-vigorous exercise kids need each day.

KUOW obtained recess data via a public records request from Seattle Public Schools; school staff and parents helped to fill in some gaps.

So why don’t schools just offer more recess?

Over the years, principals have told KUOW that they limit recess for one major reason: It cuts down on fights on the playground — conflict that staff then must resolve, which cuts into learning time.

At Van Asselt Elementary, which offers a minimum of 35 minutes a day, Principal Huyen Lam said she values recess, especially for building social skills. But she said it’s hard to fit everything in the school day.

Lam’s mostly low-income school has long blocks of instruction to help students make progress in subjects like math and literacy.

Sponsored

“Giving schools the autonomy to make decisions based on the needs of their kids, that’s the conversation that should be had,” she said, “not make it one-size-fits-all.”

At Van Asselt, kids have a 20- to 25-minute lunchtime recess, plus a short afternoon recess that's up to teachers to schedule.

Lam said she wants the district to stick to its 30-minute recess minimum, and not add to it. “Every school, every demographic, every group is different,” she said.

Another challenge for many schools is staffing the playground, which can mean hiring recess monitors, shifting staff time around, or having parent volunteers.

In Seattle Public Schools, 51 percent of black elementary students attended a low-recess school last year, compared to 13 percent of white students.

The numbers are also stark for the youngest learners. Well-off, mostly white schools tend to give kindergarten students extra recess to get their wiggles out.

Most white kindergarteners in the district get at least 45 minutes of recess a day.

Most black kindergarteners get just 30 minutes to play.

That’s the equivalent of one less scheduled recess break.

Sponsored

View Ridge Elementary, named for its position on a bluff that overlooks Lake Washington in northeast Seattle, is on the high end for recess: all students get 50 minutes to play.

Maryellen Farrokhi, who just finished fifth grade at View Ridge, said she relished all that daily recess.

“I always kind of welcome recess as a chance to take a break and help your brain and do a quick reset, so it’s ready to learn again," Farrokhi said.

Ed Roos, the principal at View Ridge Elementary, said that teachers took note. “They noticed that when the kids had more recess, they were a little bit calmer and on-task in the classroom, and so they had requested that we increase the recess,” Roos said.

He said the teachers volunteered so kids could have more time outside. “They were willing to take their own break time to supervise recess,” he said. "It was that important to them.”

At View Ridge, 2.5 percent of the students are black.

“I think it’s astounding when you look at the concentration of white students in high recess schools and the very few black students,” said Jesse Hagopian, a teacher who helped pressure Seattle Public Schools to require a minimum amount of recess.

In 2014, a KUOW investigation revealed huge racial and socioeconomic disparities in the amount of recess in Seattle schools. At the time, West Seattle Elementary School didn't have any scheduled recess; teachers decided how much, if any, to offer.

At 11 elementary schools, most of which served primarily low-income students of color, kids got just 20 minutes of playtime — or less — per day.

The following year, Seattle Education Association, the teachers’ union, bargained a 30-minute recess minimum at all elementary schools to address the recess gap.

Hagopian said it’s heartening that schools appear to be following the new policy. But he said the ongoing disparities are untenable.

The numbers “show that the district has a long way to go in bringing equity to all the public schools,” he said.

The standard, Hagopian said, should be one hour of recess a day for all elementary students.

Since KUOW started tracking recess times in Seattle, the issue has become a focus for districts – and states – across the country.

The national PTA has called for schools to increase recess times, and mandatory recess minutes have become law in several states.

And although Seattle has adopted a 30-minute minimum, Washington state has no minimum recess law.

Denise Juneau, the superintendent of Seattle Public Schools, said recess is on her radar as an equity issue, given big gaps between what different schools provide.

“Those are issues that we really need to dig into,” she said, saying there should be “equity across the board.”

Many researchers say the time for more recess is now, and that the kids who need it most tend to get the smallest amount.

“Kids from lower-income communities may not have resources in the home, or in their neighborhood, to be physically active,” Rosenberg said.

Rosenberg said physical activity has been shown to decrease depression in children, and help kids with behavioral problems cope with stress.

That’s especially helpful for kids from low-income families, Rosenberg said, who are often dealing with a lot outside of school.

Rosenberg said that some principals seem to believe that more time in the classroom will boost test scores.

“I think what a lot of schools don't realize is that they think more time in the classroom will boost achievement scores or test scores,” Rosenberg said.

Instead, she said, research shows that some of that class time would be better spent letting kids have more recess.